Analysis

"Smells Like Money to Me:" Slaughterhouses, Land Use Conflicts, and Neighborhood Identity

Louisville’s Butchertown neighborhood is a mixed residential, industrial, and commercial area that from the nineteenth through early-twentieth centuries was dominated by animal industries such as stock yards, slaughterhouses, soap factories, and tanneries. In 1892 there were more than 50 such businesses in Butchertown, which sits on 50 acres of land—less than one square mile—adjacent to downtown Louisville. Until 1998, in addition to a large slaughterhouse, there was a 20-acre stock yard in the neighborhood, where cattle and hogs were auctioned off. Today, there are three sites of animal industry in the neighborhood, including a meat distributor, a leather manufacturer, and the large industrial slaughterhouse, called JBS Swift, which slaughters 10,500 hogs per day (Butchertown Neighborhood Association v. Board of Zoning Adjustment, 2017). The Butchertown Neighborhood Association (BNA) was very active in a fight against the stock yard and continues to oppose the slaughterhouse.

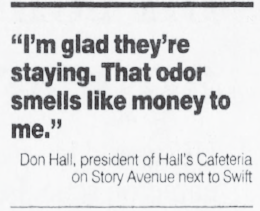

Given this history, how does the presence and decline of the dominant neighborhood industry inflect discourses circulating in the neighborhood? Louisville’s Butchertown neighborhood makes an interesting case study precisely because the largest remnant of animal industry left, the slaughterhouse, is extremely dissonant with twentieth-century U.S. urbanism. Additionally, the BNA's battles against the slaughterhouse demonstrate that they would like to fully embrace an identity as a neighborhood steeped in the history of by-gone industry, but it cannot do so until the industry is actually gone; so what discourses does this dynamic create or require? How has the neighborhood's identity changed or developed during the decline of these industries, and when and how do land use conflicts first develop?

Working at the neighborhood scale enables a close examination of the discourses that accumulate around this space, illuminating the spatialized power relations that emerge as actors attempt to influence the neighborhood’s form. Neighborhood-based land use conflicts are subject to local exigencies, and examining the discourse around these conflicts reveals some of the socio-political dynamics of capitalist production. That is, we can begin to unpack the local conditions under which it became acceptable to oppose an industry that was once dominant and on which the neighborhood’s identity—as a butchers' town—still rests. What discourses are opened or foreclosed by these local circumstances? What discourses become politically expedient and what types of influence is it possible to have over the space of the neighborhood?

Additionally, the neighborhood scale allows us to see when political actors begin to understand that economic power over Butchertown as an urban space is predicated upon separating sites of meat production and consumption, which in a postindustrial economy has become “a prerequisite in the commodification process of animals” (Neo and Emel, 2017, p. 10). That is, governance of urban space in the contemporary era requires animal bodies to be governed elsewhere, removed from the neighborhood setting. Thus, in the Butchertown neighborhood, both the commodification of animals and the commodification of former industrial sites has been disrupted by the presence of a slaughterhouse. Examining the conflicts that emerge over Butchertown’s atypical use of urban space in the postindustrial era makes this neighborhood an especially fertile area of investigation.

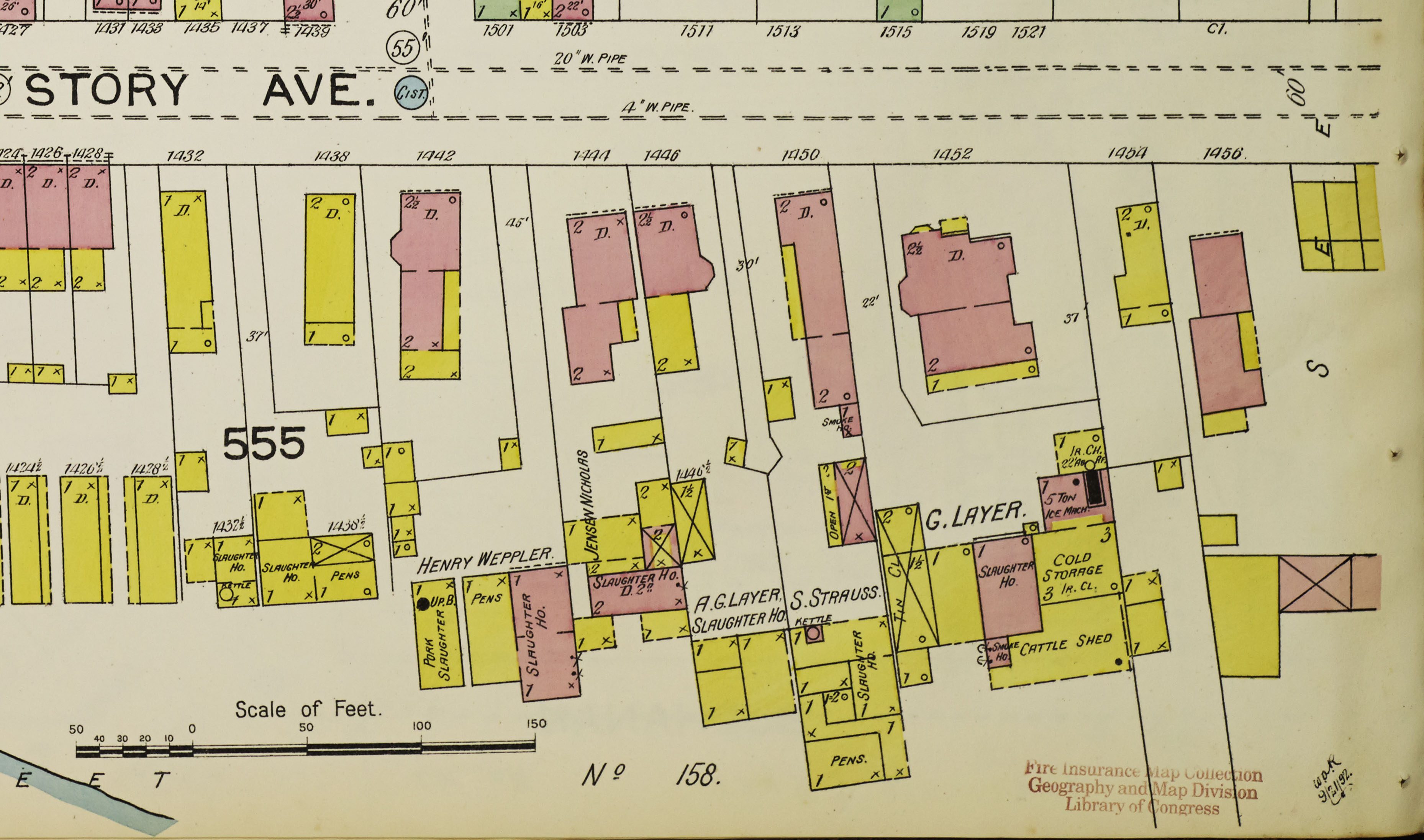

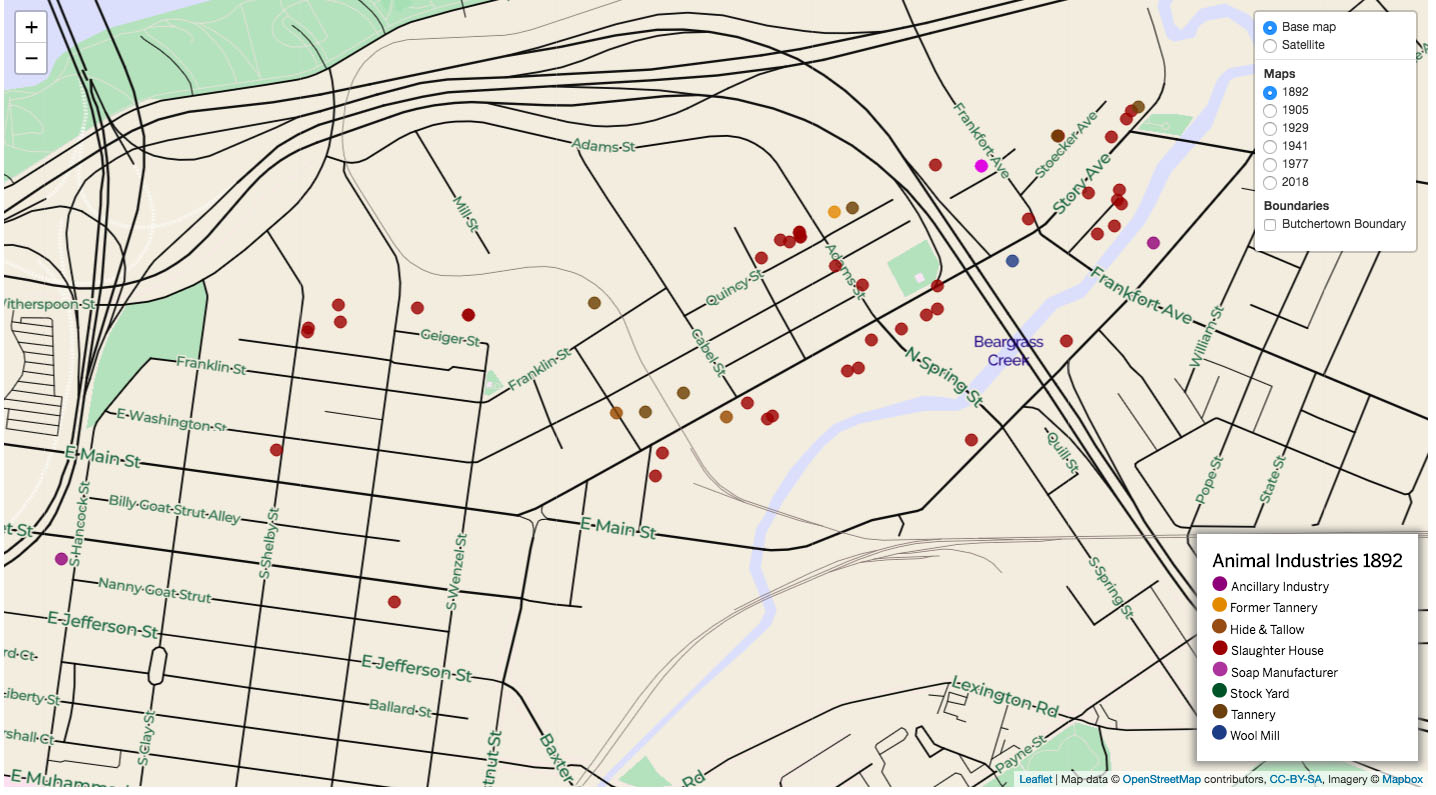

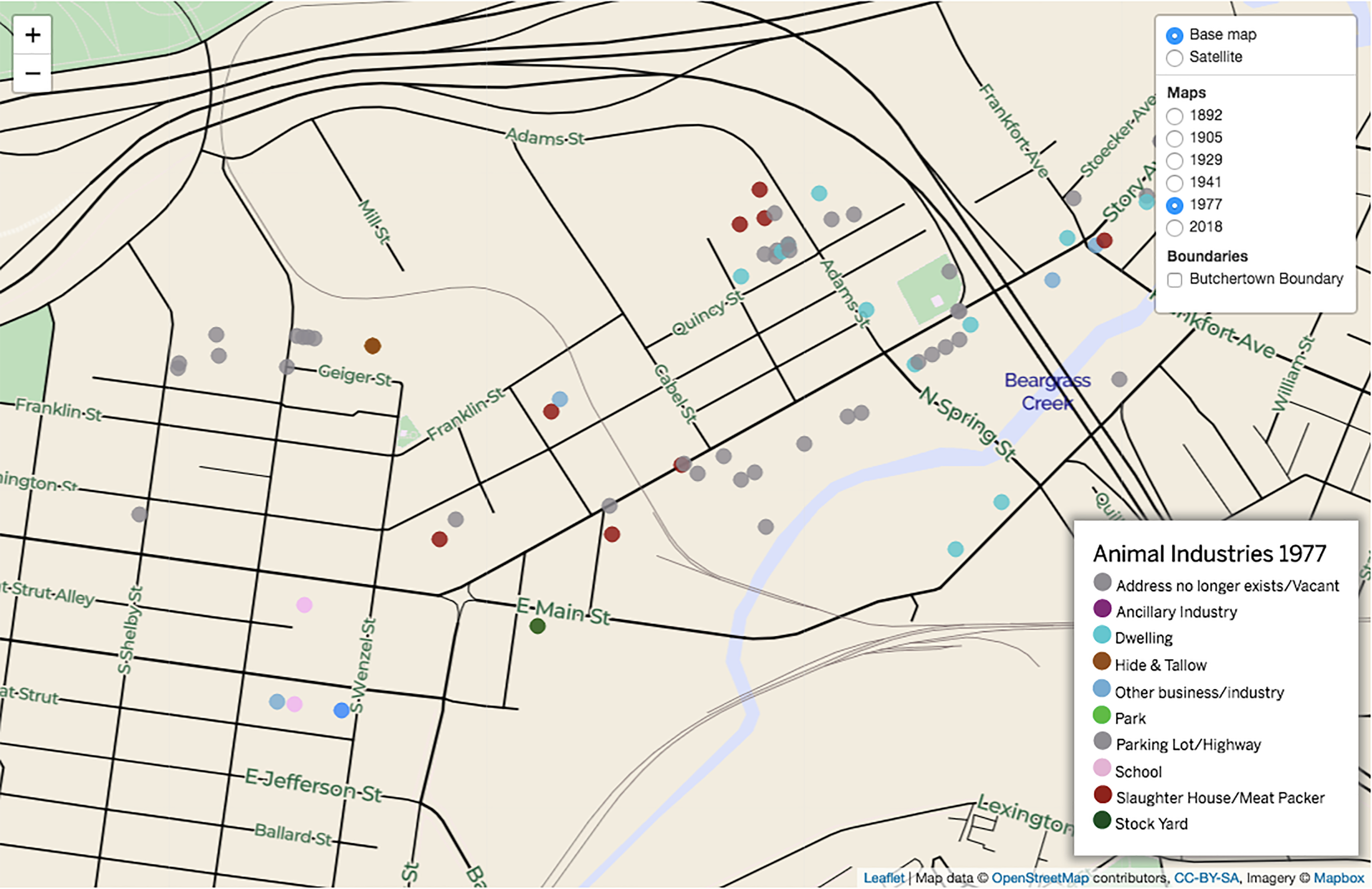

Using a combination of digital mapping and topic modeling methods enabled the discovery of spatialized discourses circulating in the neighborhood. The digital map marks the sites of animal industries beginning in 1892, a transitional time in Louisville when large slaughterhouses began to emerge, but many smaller home-based operations still remained (Kubala, 2010). The map traces these sites through the twentieth century, identifying not where the slaughterhouses went, but what happened to the spaces once occupied by animal industry. I used Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps and Caron's Louisville City Directory to identify the sites. I chose the years 1892, 1905, 1929, 1941, 1977, and 2018 because those were the years for which Sanborn maps are available; the detailed Sanborn maps present an opportunity to depict informal slaughterhouses located behind people’s homes, which were not listed in the city directories.

The Map

Visualizing the neighborhood using digital mapping allowed me to see the density of animal industries in the nineteenth century, as well as the fact that by 1929, most of the small slaughterhouses and tanneries located behind dwellings were gone and had been replaced by industrial-scale operations. The effects of Urban Renewal can be seen on the 1977 map in the sharp increase in vacant lots, addresses that no longer exist, and parking lots.

Though the map represents sites of businesses rather than the lived experiences of the commodified animals or the people laboring in these facilities, representing changes to the neighborhood form identifies the spaces in which these bodies moved and the ways certain actions were foreclosed by the predominance of certain forms (Kwan, 2007). For example, the dominance of large-scale slaughterhouses, as depicted on the 1929 map, meant workers were laboring in an industrial setting, rather than from their home; this was a shift in the social and family life of the neighborhood. Additionally, the destruction of homes during Urban Renewal in the 1960s meant fewer housing options in the community. These changes to the urban form have impacts that can be seen in changes to discourse circulating in this space; the map serves as context for the topic model, providing a spatial representation of changes to the neighborhood that were experienced by the people who lived and worked there.

The Topic Model

I topic modeled articles about Butchertown that appeared in Louisville’s Courier-Journal newspaper between 1892-1999. An article was “about” Butchertown if it substantively discussed the neighborhood itself, rather than mentioning it in passing. This method produced a corpus of 380 articles; the majority were published 1980-1999. I grouped the articles by year and used MALLET to train the topic model for those files. The topics generated by the topic model provide some preliminary findings that will lead me back to the texts themselves in order to unpack the specific discourses at work.

The topics point us toward discourses being deployed within the space of the neighborhood. Underwood uses the term "discourse," rather than topic, for the product of a topic model; he argues that the word clusters produced by Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) are not semantically unified topics, but rather discourse in the sense of the “kinds of language that tend to occur in the same discursive contexts” (2012). I’m here subscribing to Underwood’s view, and also deploying the word discourse as used in Foucault’s framework, that is, with the understanding that discourses embody, create, represent, deploy and foreclose certain behavior, utterances, social relations, and power structures (Foucault, 1978).

The discourses circulating within Butchertown depict a neighborhood developing an identity in relationship to state governance structures and to industry from the 1950s through the 1970s, and then using that identity to oppose certain types of land use—animal industries but also other sites such as a “halfway house” run by a prison company—starting in the 1980s. The late-twentieth century land use conflicts were contentious, occasionally leading to court battles (Cross, 1985). As Harvey describes, capital accumulation must continue in the built environment left behind by industry, and the control over these spaces is a potent nexus of political power (1985). In this framework, land use conflicts erupt when there is disagreement over the best way to extract value from the built environment, as can be seen in Butchertown.

Zoning & neighborhood social life: zoning mrs commission beer german units park annual apartment tour fair big oktoberfest leib days pounds trucks drive social houses

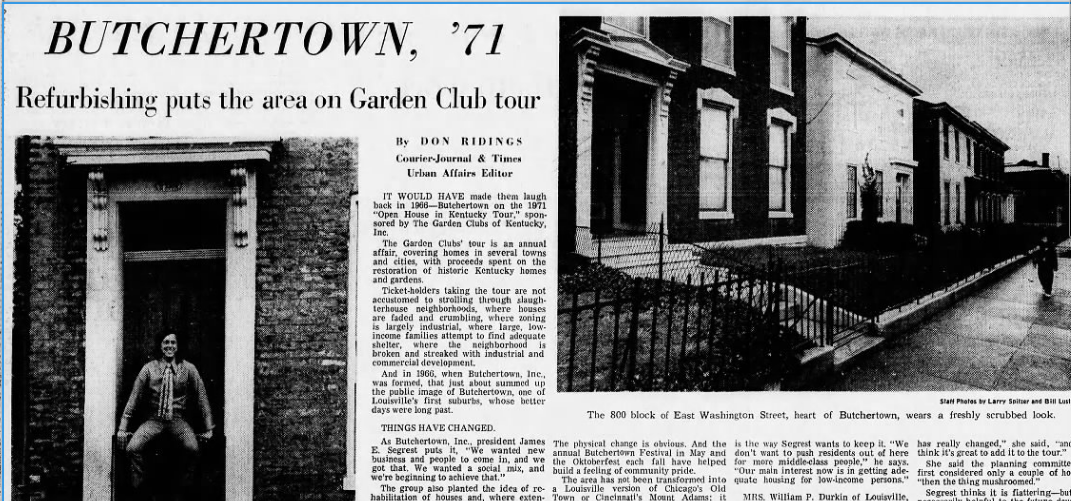

Historic Preservation: zoning law ordinance houses young historic mrs hadley row pottery james segrest restoration union live louisville’s court adjustment regulations preservation

Urban Renewal: area program poverty houses rehabilitation urban zoning poor restoration settlement cities programs planning williams staff warner renewal carle application projects

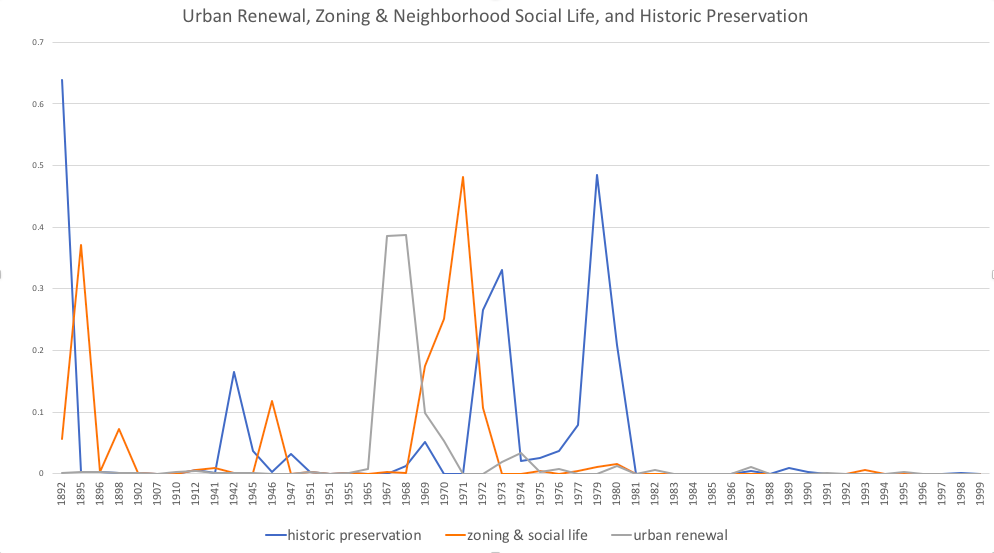

I grouped these three topics because they represent several prominent urban development strategies: historic preservation, urban renewal, and development of the neighborhood’s social life. Taken together, these topics represent the "Urban Development discourse." Creating neighborhood social activities is not exclusively a development practice, though it is often deployed as such; in this case, the topic I’ve called “zoning and neighborhood social life” includes the words "zoning," "commission," and "houses," which indicates a co-occurrence with development language and thus the use of social activities as a development strategy.

Historic preservation is a postindustrial urban development strategy and entails creating neighborhood identities in the service of “place-making” (Blokland, 2009). The Historic Preservation discourse includes the word "young," pointing to the presence of glowing articles about young couples moving to the neighborhood to renovate historic homes (‘restoration’). Specific businesses are mentioned, like Hadley Pottery, which moved into a former wool mill, as are specific political actors, such as James Segrest, who was called a “tireless Butchertown preservationist” in his obituary by the Courier-Journal (Boxley, 2014). Zoning makes an appearance in this topic as well.

The Urban Renewal discourse contains fewer words that are specific to the neighborhood and its residents, favoring more general language such as ‘cities,’ ‘projects,’ and ‘poverty.’ This indicates the presence of a top-down program that is impacting multiple neighborhoods. There is also a recurrence of ‘restoration,’ and ‘zoning’ in the topic.

The topic model shows that the discourses around historic preservation and zoning & neighborhood social life are rooted in the late nineteenth century, which does beg some questions about these topics as an "urban development" discourse as I have construed it. Yet, considering the close relationship between nostalgia, historic preservation, and urban development (Duffy, 2010), it is interesting to see the lineage of these discourses represented in the earliest parts of the corpus. There is another spike in these discourses in 1942, when residents started complaining about the animal industries ("At their doors," 1942). When viewed alongside the map, it is apparent that these complaints against the industries only appear after the scaling-up of the industries within the neighborhood had affected a separation between work and home; Butchertown became the object of new expectations around the urban neighborhood as a site of the home as distinct from work.

These discourses, most prominent from the 1950s-70s, demonstrate increasing interactions between neighborhood residents and city officials on issues such as zoning, infrastructure, and federally-funded programs. During this time, the neighborhood’s animal industries contracted further and many of the structural remnants of the slaughterhouses were demolished. I am positing that taken together, these three discourses reflect the development of the community’s identity; as the residents and business owners interacted more frequently with city officials, an identity was formed in order to communicate and realize a new need—the need to extract value from the remaining industrial structures.

Slaughterhouse Conflict

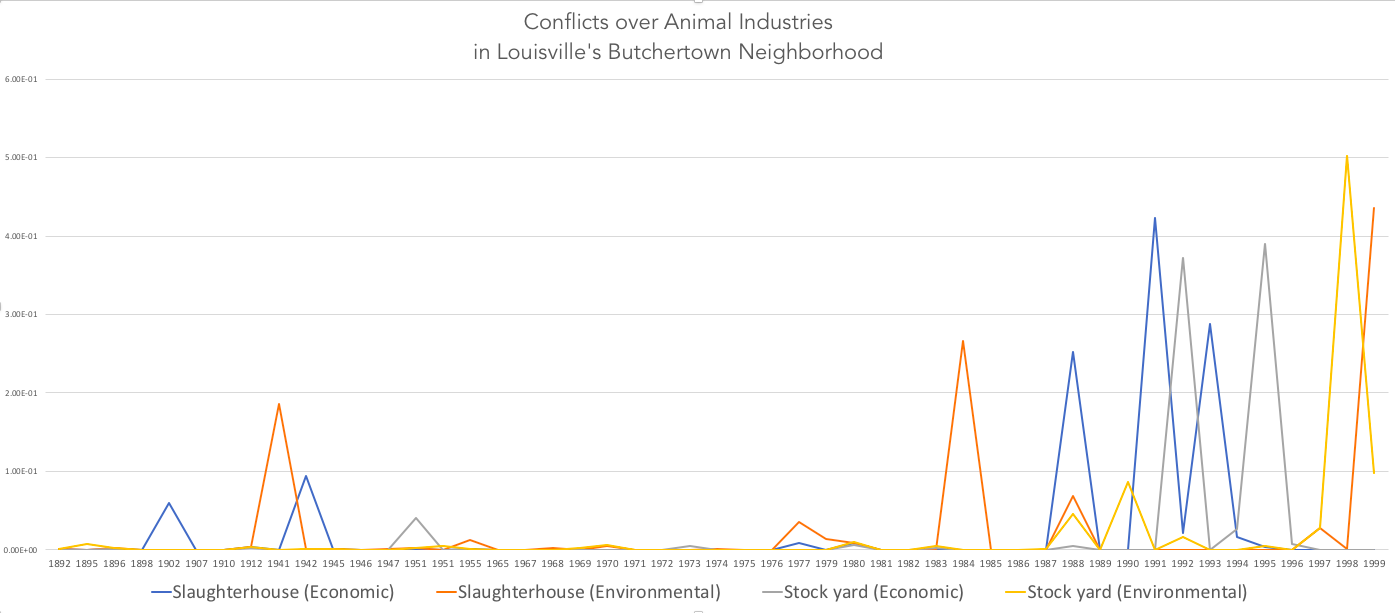

The Butchertown Neighborhood Association’s activism against the slaughterhouses and stock yards is represented by two distinct discourses: politico-economic and environmental. The politico-economic discourse typically appears first, followed by the environmental discourse. In some cases, the two appear simultaneously. The stock yard and slaughterhouse are each represented separately in the topic model, and each have both a politico-economic and environmental discourse, representing 4 of the 20 topics in the topic model.

Politico-economic: monfort edison smell armour people plant control pollution problem enterprise oertels trucks tichenor group warren jobs return tour ave kahn

Environmental: monfort plant odors creek association pollution control facade odor-control odor equipment stench waterfront air church armour district problems problem streams

Stock Yard Conflict

Politico-economic: stock market farmers yard stockyard bourbon produce homeless business cattle turnier square-foot producers livestock creation innocents year-old year-round auction love

Environmental: creek trail home road stockyard beargrass check-in river construction innocents yard hill children village acre stockyards bruker-corwin park children's volunteers

Both discourses mention the smell, odor, and pollution, which was the Butchertown Neighborhood Association's central argument against both businesses. But in the environmental discourse, specific natural features are mentioned, including the "creek," referring to Beargrass Creek (where the original slaughterhouses dropped their offal). The river, waterfront, streams, and manmade features designed to take advantage of the environment such as the "trail," are also mentioned. "Bruker-Corwin" refers to Barbie Bruker-Corwin, an environmentalist in Louisville who organized clean-ups of the polluted Beargrass Creek.

The political-economic discourses mention specific political actors, such as Bourbon Stockyard, Monfort and Armour (the companies that owned the slaughterhouse before the current owner, JBS Swift), and businesses such as Oertels and Tichenor Group. The mention of the words "district," "enterprise," and "square-foot" also indicates the presence of economic development language around urban enterprise districts and land use.

There are many avenues of investigation opened by the topic model. Returning to the texts to learn more about these two discourses will reveal how they are deployed; are there factors that make one discourse more politically expedient than the other? Are there separate factions within the neighborhood seeking to both remove the animal industries and control what happens when they leave?

Conclusion

The topic model suggests that it was not until the neighborhood had organized itself in the face of the city’s political processes and officials that the Butchertown Neighborhood Association was ready to combat the historically dominant industry, which gave the neighborhood its original identity. Thus, political experience and an identity in the political arena was perhaps a necessary precursor to combatting the historically situated animal industries. The BNA’s opposition to the animal industries meant that it had to disrupt the neighborhood’s original, historic identity while at the same time preserving that identity in order to maintain the claim to historic neighborhood status. Today, there are still signs of this fraught relationship between the area’s historic identity as a butchers’ town and the contemporary industrial reality of the slaughterhouse. For JBS Swift’s part, it is actively engaging in this debate by reminding the community of the neighborhood’s historic identity.